Translational Physiology: How Scientists Are Turning Research Into Treatments

Researchers are using animal models, human organoids and innovative therapies to address critical health issues, including diarrhea, heart disease and neurological disorders.

By Jennifer L.W. Fink

From the clinic to the lab, Mark Donowitz, MD, has built his career around one goal: unraveling the mysteries of human physiology to improve health. Donowitz’s journey began on the front lines of patient care, but it was in the laboratory during his medical fellowship that he found his true calling: decoding the complexities of digestive physiology. There, he unearthed the vital role of sodium absorption in gut function and its link to diarrheal diseases, working first with mouse and rabbit models and then with cells. He also helped apply human organoid systems—cell culture models made from normal human intestines—to advance the understanding of digestive physiology and pathophysiology (and potential treatments).

“That led us to a new understanding of the diseases,” says Donowitz, professor emeritus of medicine and physiology at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine and past president of the American Gastroenterological Association. “We were able to suggest that you could have more success in developing drugs if you took what was known from the cancer cell lines and animal models and then showed in the humanoid models that there was similar safety and efficacy.”

His research not only advanced the collective understanding of digestive physiology but led to the development of two promising therapies for diarrhea: a drug now beginning human trials and a peptide that may help treat a broad spectrum of diarrheal diseases by enhancing sodium absorption.

Translational physiology is a multidisciplinary field dedicated to improving human health. Physiologists are well-positioned to translate lab discoveries into practical interventions that improve individual and public health. From diagnostics to therapeutics, their work bridges the gap between research and real-world application.

The Heart of Translational Research

Lara do Amaral-Silva, PhD, assistant professor of biology at Wake Forest University, doesn’t work with humans (or human cells) at all. Her current research features birds; past subjects have included American bullfrogs and Tegu lizards. But her work with animals is grounded solidly in a desire to find solutions to problems that plague human health.

“Animals have cool adaptations that allow them to overcome stressors that otherwise cause major human health issues,” Amaral-Silva says. “So, if we study and understand the mechanisms that help them avoid a disease state, we may find ways that humans can be treated.”

Many well-known medical breakthroughs have resulted from careful study of animals. Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, now commonly used to treat human hypertension and heart failure, sprung from research into the venom of the Brazilian Viper. Semglutide, the currently popular weight-loss drug and diabetes medication, was born from Gila monster saliva. Scientists identified a hormone-like molecule in the saliva that stimulated insulin secretion and realized it wasn’t quickly metabolized by the body. The rest, as they say, is history.

Amaral-Silva has studied bullfrogs and birds because both animals have interesting metabolic adaptations to tolerate prolonged hypoxia, while such oxygen deprivation results in morbidity and mortality for humans. Her research pointing to the importance of NMDA receptors in maintaining brain health won the 2024 FaunaBio Translational Research Award from the APS Comparative & Evolutionary Physiology Section.

Besides studying mechanisms to avoid the neurotoxic cascade that arises from hypoxia, Amaral-Silva is also interested in birds because “they are physiologically comparable to a human that has type 2 diabetes,” she says. “They have really high glucose and insulin resistance—traits that are related to cognitive diseases and declining cognitive performance in humans—so we would like to understand how they avoid that.”

The desire to understand and improve human health is the commonality that links translational researchers, regardless of the site or focus of their work. For some researchers, that desire is based on clinical experience. Viswanathan Rajagopalan, PhD, is associate professor of biomedical sciences at the New York Institute of Technology and vice chair of the APS Translational Physiology Interest Group and a member of its steering committee. He began his career as a physician’s assistant at India’s premier tertiary care cardiovascular institute. He enjoyed working with patients in both inpatient and outpatient settings but saw so many challenging and unanswered questions in cardiovascular care.

That experience led him to study cardiomyopathy, right ventricular function and failure, anticancer chemotherapy-induced cardiotoxicity, and the interplay of endocrine hormones on cardiac physiology. Currently, he’s researching the roles of noncoding RNAs in cardiovascular, thyroid and associated disorders.

Although clinical experience inspires and informs his daily research and actively remains in his background, clinical questions aren’t always top of mind, Rajagopalan says.

“If we constantly ask clinical questions, we may not be able to answer key questions at the molecular, cellular and organ levels. So, when I study molecular physiology, including the use of human cells and tissues, I ask directly relevant mechanistic questions and, incrementally, the physiology helps us get to the patient. Physiologists are uniquely positioned to bridge molecules, humans and public health,” he says.

Finding Questions

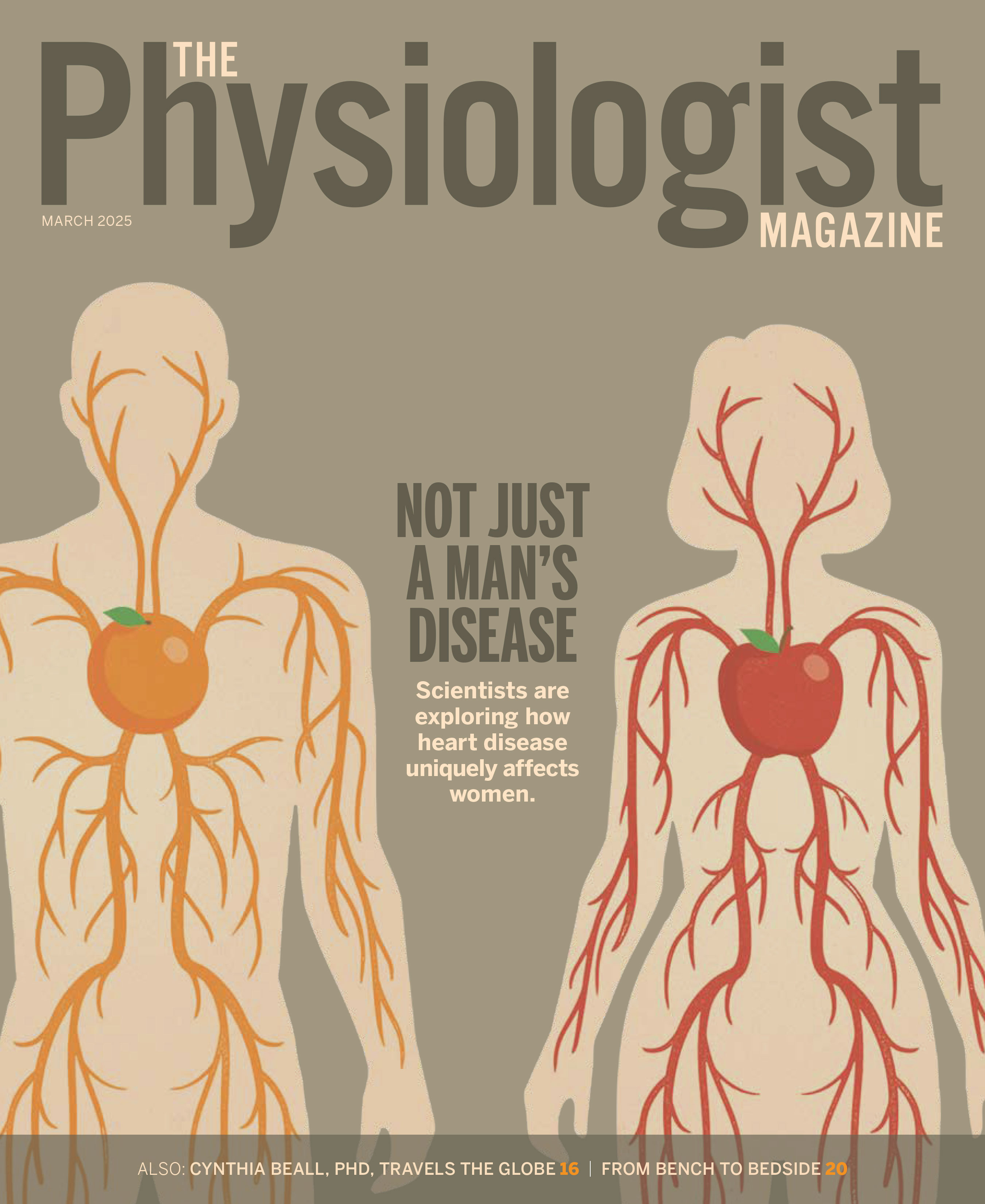

Toggling focus between patients and physiologic discoveries is key to translational research. Clinical experience is not necessary but can be helpful. A physiologist’s personal experiences with health and health care may also inform their research. Amanda Jo LeBlanc, PhD, also studies the cardiovascular system with an eye toward improving human health, but unlike Rajagopalan, she does not have clinical experience. Her focus instead grew out of a personal desire to better understand how sex and aging affect cardiovascular health.

“It was a very selfishly motivated line of research; I am a woman, I’m going to get older,” says LeBlanc, professor in the Department of Cardiovascular and Thoracic Surgery at the University of Louisville and programming chair of the APS Translational Physiology Interest Group. So, she seized the opportunity to work with Judy Delp, PhD, a pioneer in the study of women’s heart health.

LeBlanc encourages other physiologists to include understudied populations in their research. “If you have not previously used female mice or a female model, add a few extra groups to your study,” she says. “Whether you find something that’s different or not, we’re still learning. If it turns out that there’s no difference between the male and female model, that’s absolutely information we need to know.”

As LeBlanc’s research revealed more about the function of cardiac microvessels, she turned her attention toward interventions that “may make those small vessels of the heart look more like a young heart.” She is currently studying the impact of diet, genetic modifications and cell therapies on the microvessels of aging rats.

Collaborating to Find Answers

Because there are so many steps between the bench and the bedside, connecting with clinicians and scientists in other fields is helpful. To facilitate collaboration, the University of Louisville has started research interest groups that pull together people working in related but distinct fields.

“That’s helped tremendously,” LeBlanc says. “I can give a short talk about what I’m currently working on and a kidney researcher in the audience may ask, ‘Does that work the same way in the blood vessels of the kidney as in the heart?’” Such questions may sharpen research questions, suggest previously unconsidered ideas and spark productive multidisciplinary collaborations.

“Singularly focused projects with one main principal investigator are increasingly rare today. What’s more common—and getting more funding—are multidisciplinary teams,” LeBlanc says. Her most recent R01 grant includes cell culture work and human clinical trials, in large part because she’s found collaborators who do clinical trials and can recruit patients.

Working with experts in other fields can be tricky, however, as each field has its own jargon and body of knowledge. Additionally, clinicians are often busy with patients and may not have dedicated research time. Use simple, straightforward language when working with collaborators and check for understanding. Clarify as needed.

“Be patient, persistent and perseverant in trying to find the right collaborator—someone who also has time and interest in your research,” Rajagopalan says. “It’s also important to remember that they don’t have to know all the nitty-gritty things that we do and vice versa.”

Playing the Long Game

It takes time—an average of 17 years, according to some research—to translate scientific discoveries into clinical practice. And more often than not, researchers experience unexpected findings and significant frustration along the way. Maintaining forward motion can be challenging.

“In the lab, we’re faced with ‘Am I going to stop this project here or can I take it to the next level?’” Rajagopalan says. He encourages scientists to think about what they can keep doing on the side to advance their research, even if funding falls through, so that when a fitting grant opportunity eventually arises, they’ll be prepared to seize it.

Celebrating successes is helpful, as is remembering your why. “There’s still a half a million kids dying of diarrhea every year. Having that as motivation prevents me from really feeling discouraged about what we’re doing,” Donowitz says. “I’m also tremendously interested in the scientific questions. I get a high when I figure something out, and that’s kept me going.”

This article was originally published in the March 2025 issue of The Physiologist Magazine. Copyright © 2025 by the American Physiological Society. Send questions or comments to tphysmag@physiology.org.

The Physiologist Magazine

Read the Latest Issue

Don’t miss out on the latest topics in science and research.

Contact Us

For questions, comments or to share your story ideas, email us or call 301.634.7314.