Climbing Another Ladder

At NIH, Xenia Tigno, PhD, is committed to supporting women in science careers.

By Meredith Sell

As a PhD student at the University of Würzburg in Germany, Xenia Tigno had her hands full. A Filipino woman outside her country of origin, she was juggling her research and studies with marriage and family responsibilities. Her first daughter was 10 months old when Tigno and her husband arrived in Germany in 1979. Both parents were furthering their education: Tigno by pursuing a terminal degree in natural science, her husband by entering a neurosurgery residency. Their families and support systems were a continent away.

“In Germany, they already had thought of these caregiving things,” Tigno says. “They had what they called Kinderkrippe, so you can put your baby in [daycare], the nuns will take care of them for the day, and then you take them back. Unfortunately, my daughter didn’t like to be in the Kinderkrippe, so at one point I had to bring her with me to the lab.” Tigno set up her daughter’s playpen and continued her research. “It was very, very challenging.”

Now the associate director for careers at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Office of Research on Women’s Health (ORWH), Tigno directly draws from her own experience—and the experiences of her grantees and others she knows in the science and medical communities—to inform policies and new grant opportunities specifically aimed at supporting women in science.

Since she took the job in 2020, just before the COVID-19 pandemic, the ORWH has launched a variety of funding opportunities that seek to address the points in a scientist’s career that Tigno refers to as “precipices where women usually fall off.” While men can also apply to the funding opportunities, they are designed with the needs of women in mind.

“For instance, we have what we call a continuity supplement,” Tigno says. “During your career development award or during your first R01—where you’re very vulnerable because you don’t know whether you will get a second big grant—say you delivered a baby and now you have to go on maternity leave. What do you do? Your cells need to be fed or your clinical trial has to go on.” To address such situations, the office provides a one-time supplement award so that the grantee can hire somebody to do the work while they’re out. “That way they don’t lose the pace of the work and they remain competitive.”

It’s common for women in many fields to take years off due to family responsibilities. As the go-to caregivers for children and aging parents, women often have obligations, even if temporarily, that limit how much time they can devote to research or grant applications. For those who take time off, the gap in their working years can present an obstacle to future career advancement. When they return to their field, these women may feel like they’re starting over completely.

That experience is familiar to Tigno. Although she worked through the childhoods of her three children, when she moved to the U.S., she left behind a well-developed career of multiple decades at the University of the Philippines. She was a professor and chair of the Department of Physiology at the College of Medicine, the only faculty member at the time who had a PhD (as opposed to an MD). In 1997, she set up the University of the Philippines’ first translational lab, the Center for the Enhancement of Human Performance, which received support from the country’s congress, department of labor and eventually the president of the Philippines.

She was at the top of her game there, but that didn’t translate to landing a full professorship or chair position in the U.S. She had to climb the academic ladder twice.

Emigrating to the U.S.

Tigno originally came to the U.S. because of her son, who was in high school in the early 2000s. He was attending a competitive science-focused school in the Philippines. “He didn’t flunk anything,” Tigno says, “but his drumbeat was different from the rest.” He was a gifted child, but he also had Asperger’s syndrome, which his school wasn’t equipped for.

Over summer vacation in 2001, Tigno brought her son to the U.S., where they visited her sister in Maryland. They learned about the resources schools offered for students on the autism spectrum. “I thought, ‘My goodness, this is heaven-sent,’” Tigno says.

“People are starting to wake up to the fact that women’s health really is important and it should no longer be ignored. This is a golden opportunity for the field to expand.”

On the same trip, Tigno met Barbara Hansen, PhD, and visited her Obesity, Diabetes and Aging Research Center at the University of Maryland School of Medicine. Tigno’s PhD work had focused on microvascular physiology, which naturally related to the study of diabetes and the complications it causes in patients. “[Hansen] needed somebody who was a little bit more senior to oversee some aspects of the lab,” Tigno says. “She convinced me that if I wanted to stay, I could join her lab.”

Tigno and her son moved to Maryland; her husband followed a few years later, after their two daughters finished their degrees.

In 2005, Hansen’s lab transferred to the University of South Florida in Tampa, and Tigno followed. Soon after, Tigno was given the opportunity to coordinate the physiology course in the university’s College of Medicine. She had already done this type of work as the department chair at University of the Philippines, so she harnessed her experience to make the course more engaging and relevant to students who were primarily focused on passing their medical school entrance exams.

Joining NIH

A few years into her time in Tampa, Tigno collaborated with colleagues on a research experience for undergraduate students focused on women’s health. Open to honors students, the summer course provided an introduction to sociocultural and medical aspects of women’s health, as well as an opportunity to conduct research in the College of Medicine.

“Right now, sociocultural determinants of health are very much in, but at that time, they weren’t,” Tigno says. “But we had already introduced the concept that not everything that influences health is only biological—a lot of it is due to the sociocultural environment that you came from.”

This was one of Tigno’s first official efforts focused on women’s health. When she returned to the Washington, D.C., area for a grant administration role in the National Institute of Nursing Research and later a similar role with the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI), she was eager for the next chapter of her career. After about a decade of grant-making, she reinvented herself again with a revived focus on women’s health and women in science.

In 2015, Tigno’s current boss, Janine Clayton, MD, director of the ORWH, co-authored an article in Nature with then-NIH Director Francis Collins, MD, PhD, declaring that sex as a biological variable would now be considered in the evaluation of applications to the NIH. “That was a big step forward,” Tigno says.

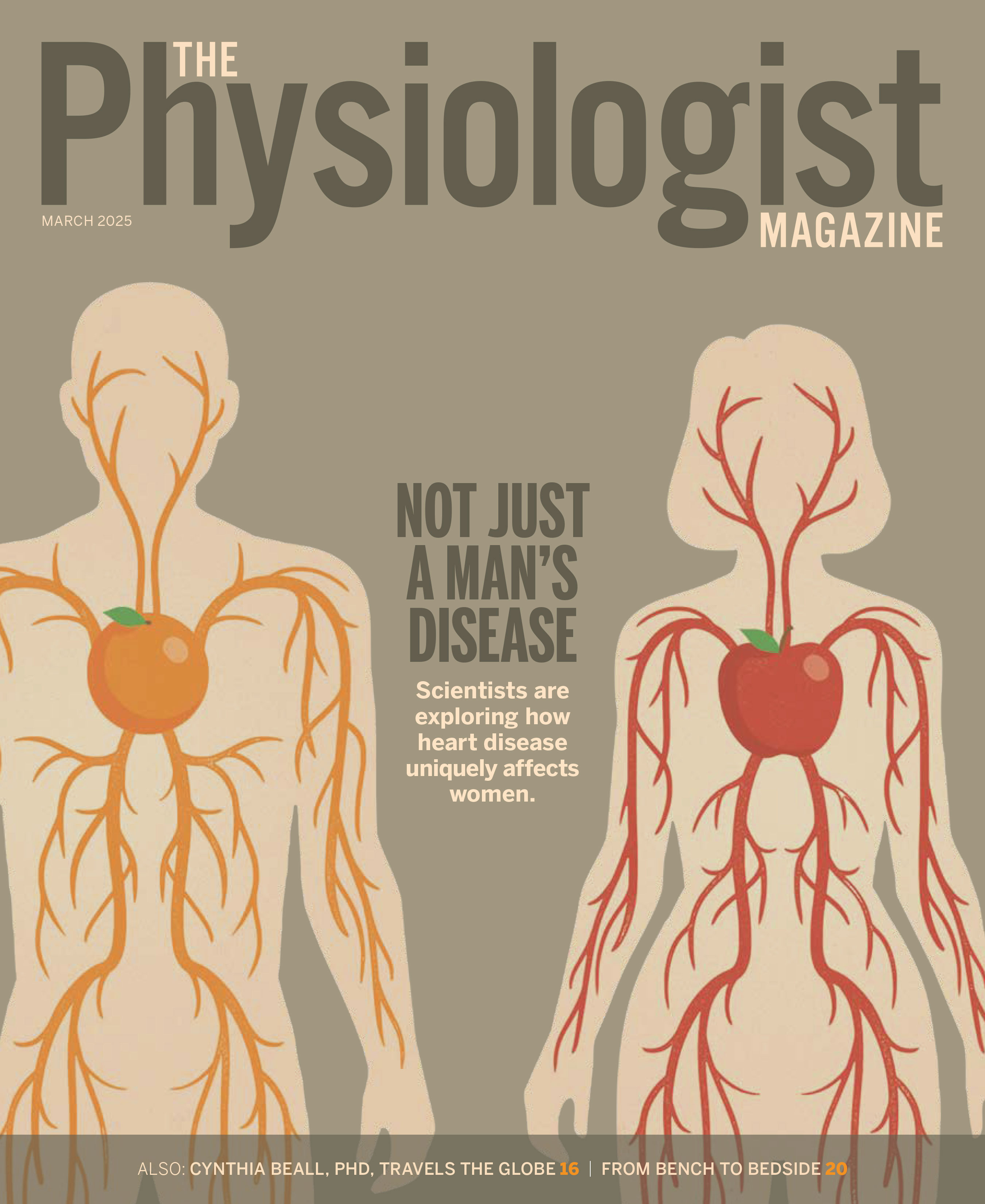

Historically, researchers have studied male subjects, whether rats, mice or humans, arguing that male subjects are more homogeneous, and thus easier to study, because they don’t have an estrogen cycle. Along with neglecting the reality that males have their own hormone cycle, this approach also ignored female physiology, leaving many women and their health care providers in the dark about how different conditions and medications affect women’s bodies.

Women’s health, Tigno says, is not just about breasts and reproductive organs, but “the entire human being, the entire woman from head to toe. Mental health is included, substance abuse is included, heart disease is included, lung, everything. Because women are not little men; they’re a completely different physiological makeup.”

Because of this, the ORWH isn’t tied to one particular institute within NIH. It’s part of the Office of the Director, an intentional decision so that its policies will affect every institute and center within the broader organization.

Advocating for Women

Tigno’s official role is focused on the careers aspect of the ORWH, but she also advocates for the inclusion of women’s health in the teaching of physiology and has recently co-edited a couple of books specifically focused on sex differences in disease. The first, “Sex-Based Differences in Lung Disease,” she co-edited with a former grantee from her time at NHLBI. This year, she is working on a similar book on cardiovascular disease, another project tied to NHLBI that taps leading researchers to write about cutting-edge issues and current science regarding cardiovascular health, sex and gender.

Tigno points to how certain conditions, such as autoimmune diseases and long COVID, predominantly affect women but that researchers don’t know why. One of her goals is to prompt scientists to naturally wonder how what they are studying affects men versus women and whether there is a difference due to hormones, chromosomes, other biological factors or gender differences. “Everything should be looked at from a sex, as well as a gender, lens, which means biological as well as sociocultural determinants of health,” she says.

Recently, more resources and attention have been given to studying women’s health. Last November, the White House announced the first-ever initiative on women’s health, and in March, President Biden signed an executive order calling on Congress to devote $12 billion for research on women’s health. While the money hasn’t come through yet and there’s no guarantee it will, Tigno is encouraged by the effort.

“People are starting to wake up to the fact that women’s health really is important and it should no longer be ignored,” she says. “This is a golden opportunity for the field to expand.”

Because many of the researchers interested in women’s health are women themselves, Tigno’s work to support their careers is crucial to advancing the field. “If you want a robust cadre of women’s health researchers,” she says, “you also have to give equitable representation to women.”

This article was originally published in the November 2024 issue of The Physiologist Magazine. Copyright © 2024 by the American Physiological Society. Send questions or comments to tphysmag@physiology.org.

The Physiologist Magazine

Read the Latest Issue

Don’t miss out on the latest topics in science and research.

Contact Us

For questions, comments or to share your story ideas, email us or call 301.634.7314.

Elevating Women’s Health Research

Women’s health has historically been under-explored. APS is proud to spotlight women’s health and research by APS members that addresses health and disease in women.