Beauty in the Simplicity

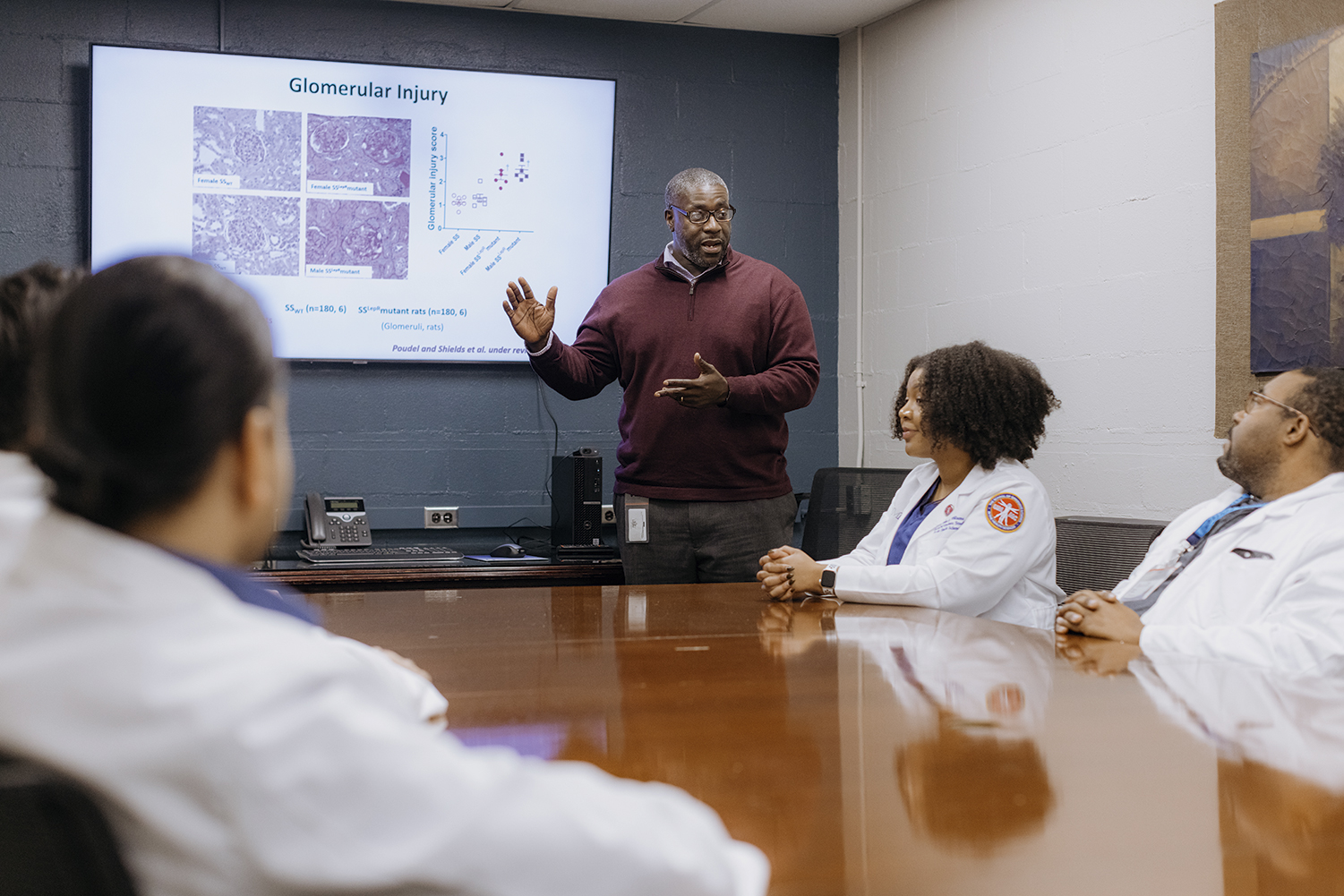

Renal physiologist Jan Michael Williams, PhD, is intrigued by seemingly simple research questions that are full of possibility.

By Rachel Crowell

For Jan Michael Williams, PhD, change has been a steady part of life. “I’m an Army brat,” he says. Williams was born on a military base in Frankfurt, Germany, and moved to the U.S. at around age 2. One year, his family moved three times within North Carolina and Georgia.

Williams credits that upbringing with helping him develop the fortitude to excel in new situations. “I’ve always looked at any transition as ‘Is it going to be a good transition for me? Is it going to help me out for my career and for the future?’ Then I’ve always adjusted very well,” he says.

By drawing on his adaptability and resilience, Williams was even able to use one of life’s curveballs—a medical emergency during his senior year of college—to discover his scientific passion for renal physiology. Williams is now a professor in the Pharmacology and Toxicology Department at the University of Mississippi Medical Center. He studies renal disease associated with childhood obesity. He is also director of his university’s experimental therapeutics and pharmacology PhD program.

Growing up, Williams always loved math. As a teenager, he discovered the joys of science, too. He fondly remembers a high school chemistry assignment that tasked him with identifying a mystery solution provided by his teacher. That experience piqued his interest in the field.

He was also inspired by observing one of his cousins, who is a pharmacist. When Williams started college at Georgia Southern University, he planned to become either a pharmacist or a chemist. An academic adviser told him that majoring in chemistry would prepare him for both careers. During his senior year, Williams was set to begin a graduate program in organic chemistry the next year. However, a sudden and jarring change to his circumstances altered his career trajectory: He developed an acute kidney injury.

“I was probably in the hospital for about two weeks, very close to being put on dialysis,” he says. Williams describes the experience as his “first time realizing how important the kidneys were.”

His plans for graduate school were derailed by the injury, as doctors recommended he take extra time to recover. During what became a gap year, he worked at Procter & Gamble as a winder operator—in charge of placing tissue paper on its cardboard roll and checking the quality of the tissue’s perforations. The only drawback to the job was that he wasn’t able to use his chemistry background, so he began researching career options in biomedical science.

Taking the extra time to recover paid off: His kidney health was restored. “Luckily, with rest and eating properly, things worked out for me,” he says. Then one day, he had an unexpected interaction with someone from the Medical College of Georgia about a PhD program he had applied to while finishing up his undergraduate degree. “They actually called me on the phone and asked me, was I still interested?”

Williams jumped at the opportunity, which he credits with putting him on a path to become the scientist that he is today. In his second year of graduate school, he joined a laboratory that was focused on renal physiology and, more specifically, the roles the kidneys play in helping control and regulate blood pressure.

Exploring New Territory

Williams also studies how obesity and kidney disease intersect in pre-pubertal children. Research into possible physiological relationships between childhood obesity and renal disease is in its infancy, he says. “We’re starting to see children with obesity develop kidney disease or have early signs of kidney disease, and nobody really focuses on that population.” However, he has seen an uptick in related research in recent years.

One key challenge in better understanding the physiology of kidney disease in children is a lack of relevant clinical data. Proteinuria, or elevated levels of protein in the urine, is often “one of the first signs of renal disease,” Williams says. But when kids go in for wellness exams, doctors may not collect urine samples. Furthermore, some families don’t have the resources to take their children to the doctor regularly, meaning missed opportunities to catch kidney disease before they reach adulthood.

“My lab has a unique obesity model that we use and have characterized very well,” Williams says. “Our rodent model develops progressive renal disease or progressive proteinuria before they reach puberty.” The researchers use the model to study various mechanisms, such as inflammation and immune cell function, in the kidney.

The lab team also looks at different aspects of alterations in renal hemodynamics before puberty, along with how insulin resistance in the kidney may play a role in early stages of kidney disease in prepubescent children with obesity.

Specifically, Williams is working with a model of leptin dysfunction. “Leptin is involved in telling the body to stop eating,” he explains. “When there is a dysfunction or deficit in this pathway, an individual or animal will constantly eat and become obese.”

One hurdle he has encountered is “trying to get the point across that this model is what we say it is.” Some researchers, he says, “just automatically assume ‘Well, it’s an obesity model. We have seen it before.’” However, Williams says his model is different for two reasons: It’s on renal disease susceptible background, and it is distinguished by its representation of the time period before the sex hormones increase.

When exploring potential research questions, Williams is drawn to seemingly fundamental questions that surprisingly open doors to new scientific inquiry. For instance, a few months ago when one of his graduate students was questioned during a dissertation defense, someone asked the student if the kidneys are insulin resistant. Before then, Williams hadn’t considered that question. Digging deeper into it, he discovered that current data suggest that the kidneys—or at least certain parts of the kidneys—may be insulin resistant. Williams is now pursuing grant funding to continue exploring the nature of insulin resistance in the kidneys.

Introverted Collaboration

Williams describes himself as an introvert, but he also emphasizes the importance of working with others to solve research problems and build community. For example, if he finds that his progress toward answering a research question has stalled, he focuses on being patient and connecting with colleagues from different research backgrounds. “It’s always good to talk with people. It’s always good to have an outlet,” he says. For him, serving as a basketball coach and mentor for kids through the Amateur Athletic Union is one of his outlets outside his work. “Get your mind away from science for a while,” he suggests.

Williams is also involved with the community-building and advocacy efforts of Black in Physiology, which is working to achieve official nonprofit status. He is president-elect of the organization, which was formed through virtual meetings during the COVID-19 pandemic and in the aftermath of the murder of George Floyd.

“Before the organization, we felt that we weren’t noticed, that we were taken for granted,” Williams says. “I think with Black in Physiology that we have knocked down a couple of doors.” The group, which is one of a growing number of “Black in” organizations, has served as a sounding board for researchers to discuss their experiences and express themselves.

Just meeting with other Black physiologists in other fields has been a new experience for many members, Williams says. When attending professional conferences, “most of the time, we don’t see people like us.” Now, “to attend an event where we’re in a room with other Black physiologists and other ethnic groups as well, to come in as one, where we can actually talk and network, has been a real benefit.”

Getting started with networking can be challenging for introverted researchers. This can be especially true for researchers who come from backgrounds that are historically minoritized in science and who haven’t had many opportunities to meet scientists with similar experiences.

However, Williams offers advice for introverted students and colleagues who want to become more comfortable approaching other researchers: “Don’t be scared to just hang out with the well-established scientists,” he says. “Be bold, get out and just have conversations with people because you may be thinking about similar ideas and questions as other scientists. You’ll be surprised how many scientists will actually just want to have a normal conversation.”

This article was originally published in the March 2024 issue of The Physiologist Magazine. Copyright © 2024 by the American Physiological Society. Send questions or comments to tphysmag@physiology.org.

“With Black in Physiology we have knocked down a couple doors. … To attend an event where we’re in a room with other Black physiologists … where we can actually talk and network has been a real benefit.”

The Physiologist Magazine

Read the Latest Issue

Don’t miss out on the latest topics in science and research.

Contact Us

For questions, comments or to share your story ideas, email us or call 301.634.7314.