Scientific Research and Women's Health

The legacies of leading women scientists are putting a spotlight on a critically important area of research.

By Amanda Bertholf

In 1918, Danish physiologist and physician Marie Krogh developed gestational diabetes while pregnant with her youngest child. As a result, she and her husband, Nobel Laureate in Physiology and Medicine August Krogh, became focused on potential treatments for the disease. Shortly after the discovery of insulin in 1922, the Kroghs became instrumental in bringing it to Denmark and spreading its use as a treatment for diabetes throughout Europe. They also founded the Nordisk Insulin-Laboratorium, which today, as Novo Nordisk, is one of the largest pharmaceutical companies in the world.

That baby born in 1918 from a line of brilliant scientists was Bodil Schmidt-Nielsen, who went on to become an eminent physiologist in her own right. During her long career, Schmidt-Nielsen, DDS, DSc, carried out significant studies on fluid and electrolyte balance and nitrogen excretion in mammalian and non-mammalian vertebrates.

In addition to her accomplishments in research, Schmidt-Nielsen was the first woman elected president of APS. This year marks the 50th anniversary of her historic election in 1974. At the time of her election, Schmidt-Nielsen said, “I think the best way I can represent women in physiology is to do my best possible job as president.”

The legacy she started of women in APS leadership continues today. Since Schmidt-Nielsen was elected, 10 other women have served as APS president, and the Society has continued to evolve, reflecting a more diverse membership and leadership. “Increasing participation of women in setting priorities for development and growth leads to an organic evolution of initiatives supported by the Society,” says Patricia E. Molina, MD, PhD, FAPS, professor and chair of the Department of Physiology at Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center New Orleans. Today, women are thriving in the Society:

- Half of APS section chairs are women.

- Nine editors-in-chief of APS journals are women.

- Nine of the 17 committee chairs are women.

- Eight of the 12 elected members of the APS Council are women.

To continue that legacy of women leading the way in science and to shine a spotlight on a critically important area of research, this year APS has launched the Women’s Health Research Initiative (WHRI). At the 2024 American Physiology Summit in Long Beach, California, nine of the past women presidents of APS were on hand to introduce the initiative, including three member advisers who are directing the effort: Janie Reckelhoff, PhD, FAPS; Linda Samuelson, PhD, FAPS; and Kim Barrett, PhD, FAPS.

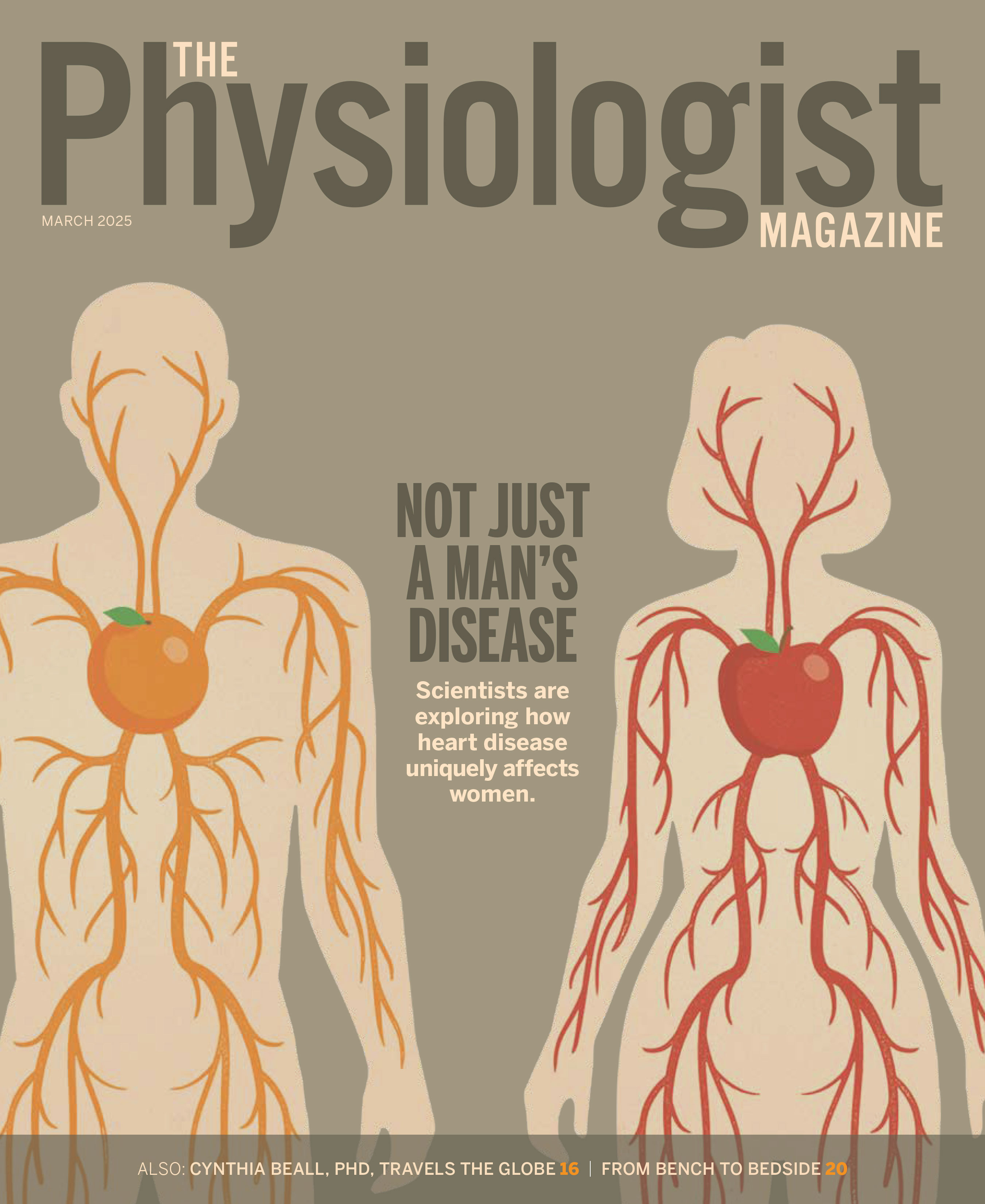

For the next year and beyond, APS will leverage the expertise of biomedical scientists and science policy and advocacy experts to elevate issues surrounding the state of women’s health research and increase the visibility of women’s health research specialties and investigators. In partnership with the Society for Women’s Health Research and National Institutes of Health (NIH), and in support of the White House Initiative on Women’s Health Research, this effort will address topics such as autoimmune diseases, breast cancer, cardiovascular disease in women, migraines, novel perspectives on sex as an investigative variable, menopause, pregnancy and postnatal conditions, and more.

The WHRI presents an opportunity to provide education and awareness of basic and translational research that may improve the understanding and treatment of diseases that affect women exclusively or predominantly, as well as gender disparities in health care. “We have a chance to highlight the importance of considering gender-specific differences in disease presentation, diagnosis, treatment and outcomes and make the world a healthier place,” says Susan Barman, PhD, FAPS, professor in the Department of Pharmacology/Toxicology at Michigan State University.

Molina says this work is important because when women spend their lives in poor health or with varying degrees of disability, it affects their ability to fulfill their roles at home, in the workforce and in the community. “They also report adverse, serious and fatal events from approved medicines more frequently than men,” she says. “Because women carry most of the burden for child care, focusing on closing the gap in sex and gender health equity will positively affect society and improve future generations’ health.”

Addressing the Gaps in Women's Health Research

Prior to the 1990s, women were rarely included in clinical trials and research studies, despite accounting for nearly half the global population and outnumbering men in the U.S. for decades. Policies aimed at protecting fetuses and pregnant women, historical prejudice, misconceptions about women’s health, and the difficulty in recruiting women for trials and studies have led to them being underrepresented in research. This has created gaps in the scientific understanding of women’s health.

“By ignoring females in research, we overlooked that the physiology of women is not always the same as that of men and that promoting women’s health may require a different approach,” says Dee Silverthorn, PhD, FAPS, Distinguished Teaching Professor of Physiology emerita at Dell Medical School at the University of Texas at Austin.

One such policy by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) was a result of the thalidomide tragedy in Europe in the early 1960s. Although it was not approved by the FDA for use in the U.S. at the time, thalidomide was available over the counter in Europe, where it was marketed as a medication for morning sickness and deemed safe to use during pregnancy.

However, it caused severe birth defects in more than 10,000 children across Europe and resulted in thousands of miscarriages. As a result, many governments and medical authorities tightened their pharmaceutical review processes. In 1977, the FDA called for an exclusion of women of reproductive potential from Phase 1 and 2 clinical trials unless they had a life-threatening condition.

Researchers and medical investigators also excluded women from studies due to concerns that their hormonal cycles would interfere with the results and would not provide a stable baseline to measure specific mechanisms against. This led to an emphasis on using male animals for studies, using experimental models or male patients—and male health getting a lot more attention.

“Most scientists back in the day were men,” says Kim Barrett, PhD, vice dean for research and distinguished professor of physiology and membrane biology at UC Davis School of Medicine. “Most organizations were headed by men. There just was a natural emphasis on men.”

Today, female subjects continue to be underrepresented in animal research across disciplines. Some researchers who conduct animal studies avoid using female mice, believing the use of females will hamper research because of the need for increased samples sizes and the increased costs. A 2018 review published in Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences found male bias in studies from eight out of 10 fields: general biology, neuroscience, physiology, pharmacology, endocrinology, behavioral physiology, behavior and zoology—reproduction and immunology were the exceptions.

Barrett says the lack of female subjects in studies has led to health care disparities. “We have such a wealth of information about physiological mechanisms and pathophysiological mechanisms and disease,” she says. “But so much of that information derives either from studies of male animals or studies of male humans.”

Making Changes to Include Women

When Bernadine Healy, MD, became the head of NIH in 1991, she pushed for researchers to include women and minority groups in all NIH-funded research. But there was a lack of funding and no enforcement mechanisms. Janie Reckelhoff, PhD, FAPS, Billy S. Guyton Professor and Chair of the Department of Cell and Molecular Biology and director of the Women’s Health Research Center at the University of Mississippi Medical Center, says this led to more attention on including women in research, but not to the extent needed.

“The data were never separated from men and women. They were all combined in one group,” Reckelhoff says. “For example, when the notable study came out that said aspirin is supposed to protect you from heart disease, well, that works in men, but it doesn’t work that way for women. What works for women is that aspirin prevents strokes. Those are big differences.”

Fast forward to 2012 when Janine Clayton, MD, became director of the NIH Office of Research on Women’s Health. She’s the architect of the NIH policy requiring scientists to consider sex as a biological variable across the research spectrum. The policy received resistance initially. But once the policy began to take effect, researchers were finding differences. “I always tell people to look—look at the animal model and see if the females and males are different, and they always are,” Reckelhoff says. “It doesn’t matter what it is. It’s exciting when you can get people to actually do the experiments.”

But there’s more work to be done. Despite policy and social changes, women remain underrepresented in research. A study published in Contemporary Clinical Trials found from 2016 to 2019, women accounted for just 41% of participants in trials. The underrepresentation is significantly higher for women of color.

“Researchers are ‘factoring’ for sex, but I have no idea what that means,” Reckelhoff says. “They are not actually looking at the men and women separately and then doing an analysis.” Reckelhoff cites the SPRINT trial which set the guidelines for blood pressure control. The studies were conducted with 60% men and 40% women, and because there were so few women in the trial, researchers did not separate the data.

The study indicated a blood pressure reading of 120 mm Hg resulted in reduced cardiovascular events. But when a group of women cardiologists analyzed the data, they found that women were not as protected from these events as men at that blood pressure reading.

“We’re still fighting this, and so that’s why it’s important to get the Women’s Health Initiative rolling right now,” Reckelhoff says. “The more that investigators hear about the fact that there are gender differences, it’s going to raise awareness.”

The Right Time

APS and the physiology research community have been out in front of this issue for decades. “Physiology research has been near and dear to my heart for the vast part of my career and in the training of the next generation of scientists,” says Jennifer Pollock, PhD, FAPS, professor in the Department of Medicine, Division of Nephrology, at the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

“Physiology is central to the practice of medicine and the creation of therapeutics to treat disease. From my perspective as a scientist, fundamental knowledge is critical to understand women’s health across the lifespan. There is not a group of basic scientists better equipped to lead this research than APS members.”

APS first sponsored a biennial conference on sex and gender 24 years ago, well before this issue was widely recognized as a gap in the health research landscape. “Physiologists have identified important sex-dependent aspects of physiologic function,” says Linda Samuelson, PhD, FAPS, John A Williams Collegiate Professor of Gastrointestinal Physiology at University of Michigan. “And now, APS and the physiology community are poised to take advantage of the recent broader recognition of the gap in knowledge to make a difference in women’s health going forward.”

Meredith Hay, PhD, FAPS, professor in the Department of Physiology at the University of Arizona, says the continued investment by APS in women’s health research is a continuation of these efforts. “This will position APS to take the lead in the national response to fulfill the White House’s new initiative to advance these areas of research,” she says.

That national response includes the White House weighing in on the importance of studying gender differences and disease. In March, President Biden signed an executive order that builds on the White House Initiative on Women’s Health Research, which was established last November. The effort is being led by First Lady Jill Biden and the White House Gender Policy Council and directed by Carolyn M. Mazure, PhD, founder and director of Yale School of Medicine’s Women’s Health Research Center.

“The White House initiative elevates the importance of women’s health research in the nation, which is really extraordinary,” Mazure said in a statement. “We have outstanding opportunities to make the progress that

we need.”

The executive order outlined actions to:

- Prioritize and increase investments in women’s health research and integrate women’s health across the federal research portfolio.

- Expand and leverage data collection and analysis and galvanize new research on women’s health.

- Strengthen coordination, infrastructure and training to support women’s health research and assess unmet needs to support this effort.

- Create dedicated NIH funding opportunities for this work.

Blazing Forward

There are bright spots on the horizon—and the future starts with the people conducting the research. More women are choosing career paths in science, and that could lead to more interest in this work. “The opportunities for women in science, including those who have chosen physiology as a focus in their careers, have expanded substantially over the last several decades,” says Hannah Carey, PhD, FAPS, professor emeritus in the Department of Comparative Biosciences at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. “From basic to translational research and advancements in the teaching of physiology, women have played key roles in the explosion of physiological knowledge that forms the basis of new developments to improve health. That knowledge also sustains animal health for domestic species and for wildlife, which are key components of the ecosystems in which we all live.”

And according to the Association of American Medical Colleges, for the first time, there are more women than men in medical school. “If I had decided to go to medical school when I graduated from college, I would have been one of three women in a class of over 100,” Silverthorn says. “Today, we are seeing more women in undergraduate biology classes, and it is spreading into graduate schools. In May 2022, more than half of our APS trainee members under age 40 were female.”

But in the end, this isn’t just about women. “This benefits men, too, because we’re better able to develop specific guidelines for health and more precision medicine that is specific to each of us, which is what we all need,” Reckelhoff says. “It improves health care for all.” A legacy that Bodil Schmidt-Nielsen would no doubt be proud of.

This article was originally published in the July 2024 issue of The Physiologist Magazine. Copyright © 2024 by the American Physiological Society. Send questions or comments to tphysmag@physiology.org.

“The more that investigators hear about the fact that there are gender differences, it’s going to raise awareness.”

Janie Reckelhoff, PhD, FAPS

The Physiologist Magazine

Read the Latest Issue

Don’t miss out on the latest topics in science and research.

Contact Us

For questions, comments or to share your story ideas, email us or call 301.634.7314.

“This will position APS to take the lead in the national response to fulfill the White House’s new initiative to advance these areas of research.”

Meredith Hay, PhD, FAPS