Family Ties

For some, physiology is more than their passion and their career path; it’s a part of their family. Some physiologists have family connections, whether the love of science was passed from parent to child, shared with siblings or helped them find their romantic partners. Physiology runs in their blood and in their family. Here are just a few of their stories.

A Triple Dose

A Triple Dose

By Lindsey Alexander

Kristen Engevik, PhD, has a beloved photo of her two older sisters, Mindy, the oldest, and Amy, the middle child. They are both in pigtails, sitting on the floor playing with a toy medical kit. “I like to think this is where it fully originated. I wasn’t around yet, so they were just waiting for me to show up on the stage,” Kristen says.

The three Engevik sisters all went on to become gastrointestinal physiologists. This happened “completely by luck,” Mindy says. Mindy and Amy are assistant professors at Medical University of South Carolina. Kristen is a postdoc at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston. All three earned their PhDs from University of Cincinnati’s systems physiology and biology program.

Amy says there were inklings, if not about physiology, about the girls all becoming research scientists. “We grew up in a rural country town, so our parents always encouraged us to be outside playing in the wilderness. … I remember my friends would be talking about all the cartoons, and we rarely watched TV growing up. We just had very different pursuits as kids I think than most people,” Amy says.

As kids, they were “really into tadpoles and frogs and rock identification and plant identification,” Mindy says.

“I really liked trying to find mushrooms on different trees,” Kristen says. Their small town of Julian, California, had a population of about 1,000, further contributing to their bond. “I spent all my time with Kristen and Amy—we had all these adventures together, so I think that also made us really close and similar,” Mindy says.

Sharing a field offers many fringe benefits: Mindy appreciates the editing. Amy likes that it triples their networks. Kristen calls their sisterhood “my help center” for manuscript edits, PowerPoint reviews and suggestions on what antibiotic concentration to use.

“It’s also a good place to vent,” Mindy says, laughing. Not to mention built-in collaborators: In the past two years in varying combinations of writers, the Engeviks have co-written 16 papers together.

Things can get awkward for

the Engeviks, such as in cases of mistaken identity. For instance, National Institutes of Health reviewers initially rejected Amy’s fellowship application because they said she’d already done her dissertation on the gut. Hers was on the

stomach. They had confused her with Mindy.

There was also that time at a poster competition when alphabetical order placed Mindy and Amy side by side. “We show up and we’re literally wearing the exact same thing,” Mindy says, recalling their navy dresses, yellow cardigans and black flats. (They now coordinate in advance.)

Overall, however, the sisters wouldn’t trade it. “I love being one of the three,” Amy says.

A Brothers’ Bond

A Brothers’ Bond

By Meredith Sell

Education was emphasized in the Rouabhi household. Growing up in Iowa City, Iowa, brothers Mohamed Rouabhi, MD, and Younes Rouabhi each caught the learning bug at home.

In elementary school, Younes picked up a book of science experiments and begged his mom to buy supplies. “She said, ‘No, but we can make our own,’” Younes recalls. So they crafted their own petri dishes and Younes wandered the house swabbing the phone, door handles and toilet seat for bacteria.

Meanwhile, Mohamed was fascinated by the human body. Their other brother, who was a year older than Mohamed, had Down syndrome, and Mohamed remembers observing the differences between the two of them. “He used to be the biggest kid, the tallest and the strongest of anybody, and early on, I passed him up,” Mohamed says. “He started not being able to be as fast and ... stay as energetic as I was.” The difference bothered Mohamed; he wanted to understand it.

The Rouabhis’ curiosity remained piqued beyond grade school, and both brothers are now pursuing careers in science. Mohamed earned his bachelor’s in human physiology at the University of Iowa, graduated from medical school at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, and is currently in his first year of residency in internal medicine at Washington University in St. Louis. Younes is in his junior year as an undergraduate biomedical engineering major at the University of Iowa and in the past couple of years has developed a stronger interest in human physiology.

“When we hit the part of the [biology two] class which talked about the human organ systems and how they all worked in tandem with one another, I remember being absolutely floored and stunned about how it all worked so cohesively,” Younes says.

His desire to do more experimental research involving physiology led Younes to pursue a 2021 APS Summer Undergraduate Research Fellowship (SURF) in the lab of Kamal Rahmouni, PhD, at the University of Iowa’s Carver College of Medicine, where Mohamed was also a SURF fellow several years earlier.

While Younes hasn’t settled on a career path yet, Mohamed appreciates having his younger brother following in some of his footsteps. He offers advice and hopes to help his brother do better in classwork and research than he did. Younes, along with feeling a sense of competition with his big brother, is grateful to be able to look to Mohamed for guidance and encouragement. “It’s something I’m really lucky to have as an undergrad and as a sibling,” he says.

Blood Lines

Blood Lines

By John Loeppky

As a child, Michael Hall, MD, spent his summers a bit differently than his peers did. While other kids were working or at summer camps, Michael was “measuring sodium in dog urines,” he says, helping out in the lab of his father, past APS President John Hall, PhD.

Michael says working with his dad had a lot to do with the career he chose as a cardiologist. He called that lab time “a fun perk,” but John remembers that his son sometimes needed a little bribery.

“He had a really weak stomach as a little kid,” John says, “so I had to tell him I would buy him a milkshake or something.”

The pair’s professional relationship has come a long way in the intervening years, from time spent on each other’s research projects to co-authoring academic papers. John is the Arthur C. Guyton Professor and Chair of the Department of Physiology and Biophysics at the University of Mississippi Medical Center, a position named after his mentor. Michael is associate professor of medicine, physiology and biophysics and the associate division director for the Division of Cardiovascular Diseases.

One recent collaboration is the 14th edition of the “Guyton and Hall Textbook of Medical Physiology.” John had collaborated on two previous editions of the text—which guides many medical students’ studies each year—with Guyton in a professional relationship that lasted more than 30 years. The elder Hall says his son’s involvement has brought a “clinical perspective” to compliment the already present academic foundation.

As for how the father-son duo worked together, John says Michael required less revision than his own attempts more than 20 years ago. “When I wrote my first chapter for the book, Dr. Guyton looked at it for about a day. And he brought me back and he said, ‘This is really great; the writing is wonderful. You did a really good job on the writing, but I need you to cut it by 50%.’ And I said, ‘Well, what 50% do you want me to cut?’ And he said, ‘You know, I don’t care.’

“His point was that it’s not written as a reference book; it’s not written for professional physiologists, that it’s written in a way that provides the critical information that medical students need.”

Michael has one piece of advice for working with family: Make sure that the career you share is an area of interest rather than just a natural progression. “In a family environment like that, it can’t be a forced deal. Fortunately, I was never pressured; it was something I enjoyed."

Love & Laughter

Love & Laughter

By Brittany King

Back in 2010, a physiologist, a physician scientist and a bunch of other scientists were in an online chatroom burning through topics, when the physician, who often tested on lab mice, said humans are the only acceptable model organism to test hypothesis. The chatroom erupted in disagreement, even from the physiologist who mostly studied humans.

That argument, and other online chats about their work, laid the groundwork for Melissa Bates, PhD, and Michael Tomasson, MD, to form a friendship and eventually a romantic relationship. The married couple have published papers together, borrowed ideas from one another’s approach to science, and currently lead a science lab together at the University of Iowa.

Turns out Tomasson’s flippant comment back in that chatroom was just that: “I really just said it to stir the pot,” he laughs. At the time, he was seeing patients with blood cancer where he was very focused on cancer biology at a genetic and molecular level. Meanwhile, Bates’ work focused on the entire organism. Open to learning a new way of looking at his work, Tomasson began to join Bates at several American Physiological Society meetings, where he realized his work with cancer patients could benefit from a physiologist approach.

“In physiology we use different levels of interrogation,” Bates explains. “It has been fun to know Michael and have this conversation of, ‘I know you think you’re a cancer biologist, but you’re actually a physiologist because you’re studying how a system responds to a stress.’”

While Tomasson often works with patients who are near the end of their life, Bates works with premature infants at the beginning of their lives. At first, they thought their work could never overlap, but as Bates began to look at the sleep pattern of infants and Tomasson the sleep pattern of his patients, they found that breathing was a commonality that both groups struggled with.

They used their separate observations to create a collaborative new research area, understanding how sleep apnea contributes to blood cancer in adults and children. “When you bring people together that approach science from different perspectives, you actually do more powerful science,” Bates says.

Today, in their lab, they promote students learning from one another, showing them there isn’t just one way to approach scientific work. “It’s natural to want to listen to other people talk on the same subject you’re interested in, but we’re coming at it from a different perspective,” Tomasson says. “Medical residents are missing the whole-organism approach. There’s a need for physiologists in medical education to help them understand the scientific method and how to do basic statistics. That crosses disciplines.”

When they’re not in the lab together, the two enjoy bike riding, hiking and watching independent films. They also have a cocktail group they join on Fridays. “The only reason our partnership in science works is because there are clear boundaries in what happens at home versus what happens at work,” Bates says.

Colleagues to Spouses

Colleagues to Spouses

By Meredith Sell

The first time Paola Casanello, PhD, encountered Luis Sobrevia, PhD, she wasn’t thinking about love or romance; she was thinking about nitric oxide.

In the late 1990s, Casanello was a midwife in Chile working in a neonatal intensive care unit, where most of the babies had been born preterm and had respiratory insufficiency because their lungs weren’t fully developed. At that time, nitric oxide was commonly used to treat premature babies’ lungs, but there wasn’t clear scientific understanding of why it seemed to help. Were there secondary effects? Could it be harmful?

Driven by these questions, Casanello attended a workshop about nitric oxide at the University of Concepcion in Chile. She remembers being surprised by how many fellow Chileans were experts on nitric oxide, a novel research topic. Sobrevia, an associate professor at the university, was one of them.

Within a couple years, Casanello pursued a master of science in physiology at the University of Concepcion and began working in Sobrevia’s lab. They had similar research interests: fetal physiology, the impact of maternal health (especially gestational diabetes and obesity) on fetal development, and the placenta. Their relationship was professional; they were colleagues, scientific collaborators.

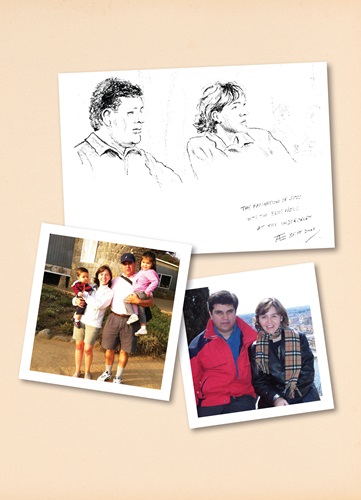

It wasn’t until fall 2001 that, Casanello says, “we began looking at each other in a different way.” They had traveled to Bristol, England, to present research at a physiology conference, and one evening, on a walk together in the city, they were caught in a downpour. They rushed inside a church to escape the rain and ended up in the crypt, listening to live jazz, eating soup and talking to each other as a church event went on around them. After a while, a couple sitting near them handed them a drawing: a rough portrait of Casanello and Sobrevia beside each other. To Casanello, it felt like a sign.

They started dating, and four years later, in December 2005, they married. Along the way, Casanello earned her PhD in physiology and both of them took professorships at Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile in Santiago.

They now have two children, a 14-year-old daughter and 11-year-old son. The family is spending 2021 in the Netherlands, where Casanello and Sobrevia are visiting professors at the University of Groningen, enjoying an academic sabbatical. They split the housework and often share notes on their research, which has helped them address different research challenges. “It feels like having my own permanent expert reviewer at my shoulder,” Sobrevia says.

This article was originally published in the November 2021 issue of The Physiologist Magazine.

The Physiologist Magazine

Read the Latest Issue

Don’t miss out on the latest topics in science and research.

Contact Us

For questions, comments or to share your story ideas, email us or call 301.634.7314.